Maths is a subject that is popularly said to come easy to some and less easy to others. While there is likely to be a large element of intrinsic capability, many of the barriers to understanding come from the ways in which the subject is taught; and these barriers can be put up from a very early age. I am committed to the idea that students learn most effectively when they have a strong element of personalisation built into their programme of study; this need not come at the expense of valuable whole-class learning, but should be central rather than marginalised.

My first proper experience of personalised learning was with the Kent Mathematics Project (KMP), which I studied at secondary school. I was fortunate enough to have a teacher, Mr Bird, who was fully engaged with the programme and quite passionate about it. By pursuing a personalised program determined by a ‘matrix’ that my teacher would assign to me, I learned maths individually and at my own pace, with the occasional whole-class lesson, and managed to get through my O level with a grade A. This was pre-national curriculum, with the ‘new maths’ of the 1970s, which included exotic topics such as topology, set theory, matrices and base arithmetic.

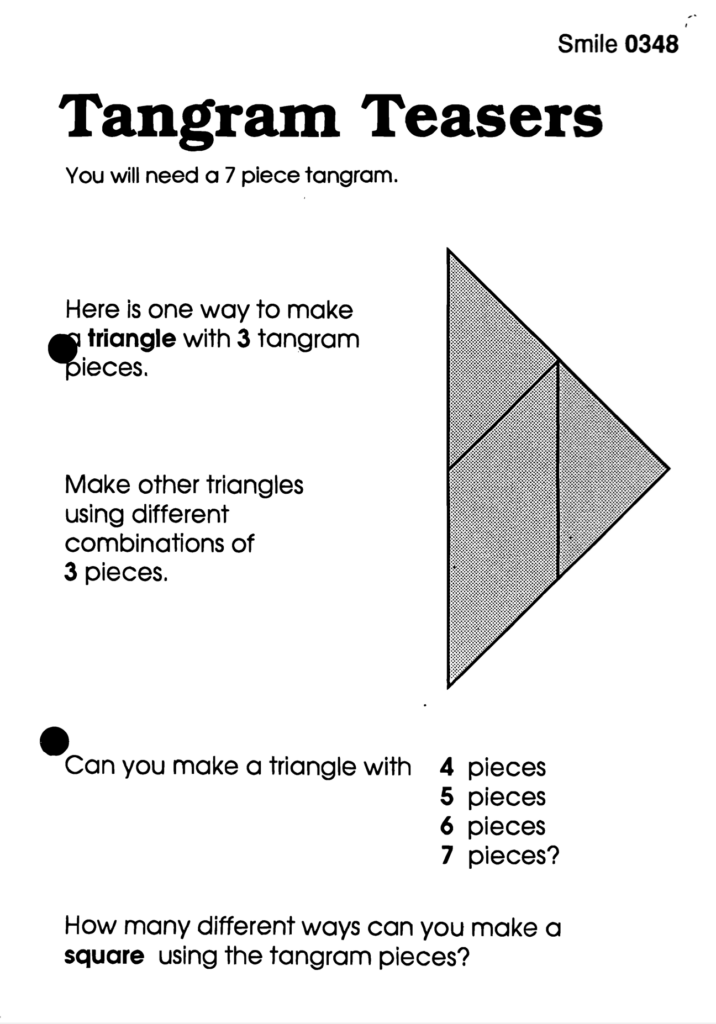

Later, as a maths teacher at Holland Park School, I taught using the SMILE program, which was based on a similar structure. Students followed a matrix of cards which was set by the teacher; each card had a unique identifier number, and looked a bit like this.

Students in mixed ability classrooms had the freedom to learn at a pace and level that suited them, and to make connections for themselves. It certainly didn’t suit all students, and here the role of the teacher was important in getting the best out of the program.

Equipment was critical as well; this is a definite challenge in personalised programs, particularly those that advocate an active approach. In this particular example, there’s lots of cutting out and gluing from templates. You need to ensure lots of scissors and glue!

At the same time, the 29 other students in the class are all doing totally different cards that involve other equipment – and you’re guaranteed not to have it all. There’s a large element of classroom management here, trying to keep everyone engaged fruitfully and learning.

There was some technology involved, through MICRO Smile with its great programs like Race Game, which now seems iconic and retro. There might just be one computer in a classroom – and one lucky student getting to use it.

During my teaching experience in FE college in the 90s, the concept of open learning was in vogue, particularly in the first half of the decade. I suppose this was a forerunner of the virtual learning environment, but largely low-tech. This largely revolved around workbooks which were organised into units, and students would individually work through them, much like KMP and SMILE; however these programs were largely geared around GCSE resits. Students who may have had a culture of failure at school, going back over it all but largely on their own, with a heavy focus on their own motivation. Left to their own devices, many students would likely fail again. The role of the teacher in drawing students together over a shared topic was vitally important, as in schools.

This was in the time of maths coursework, when a lot of the more engaging activities had relevance because students would need those investigational skills. It was also a time of modular GCSE programs, and three tiers of entry: Higher, Intermediate and Foundation. So much material was generated by so many colleges – I don’t know how much of it still exists. As time went on, and new governments came in with their own agendas, there was a move back to more traditional modes of teaching and learning

As a publisher, I have tried to incorporate elements of personalisation into my textbook series, through elements of differentiation such as in Framework Maths, which was structured around three books per year group: Support, Core and Extension. On reflection, although this series and others achieved success with the move back towards streamed classrooms, I think there is still a need for good mixed ability materials, where the differentiation is built into a much more integrated shared experience.

More suitable for a personalised delivery are digital media, which have come a long way in the last 25 years since I started in publishing. The popularity of MyMaths hinted at the potential of formative assessment models, augmented by presentations and animations. As a freelancer, I have worked on various digital platforms that are structured around pathways, either for mainstream learning or for intervention. With the latest advances in AI and adaptive technologies, the future of personalisation in the classroom is definitely exciting.